PUBLISHED

February 22, 2026

KARACHI:

For more than a week, Pakistan’s T20 World Cup campaign was framed less by cricket and more by choice. The initial decision to boycott the match against India shifted the conversation from team balance and match-ups to principle and precedent. When Bangladesh requested reconsideration, and Pakistan eventually agreed to take the field, the narrative pivoted again. The question was no longer whether the game would be played, but what it would mean once it was.

Amid that uncertainty, the team itself remained a source of expectation. Back home, fans spoke less about politics and more about possibilities. There was belief in the pace attack, confidence in experience at the top, and quiet optimism that this tournament could offer something steadier than past campaigns. In Colombo, pockets of green in the stands carried that hope across borders. Supporters who had travelled did not come to witness a diplomatic episode. They came to watch a side they believed had the tools to compete with anyone.

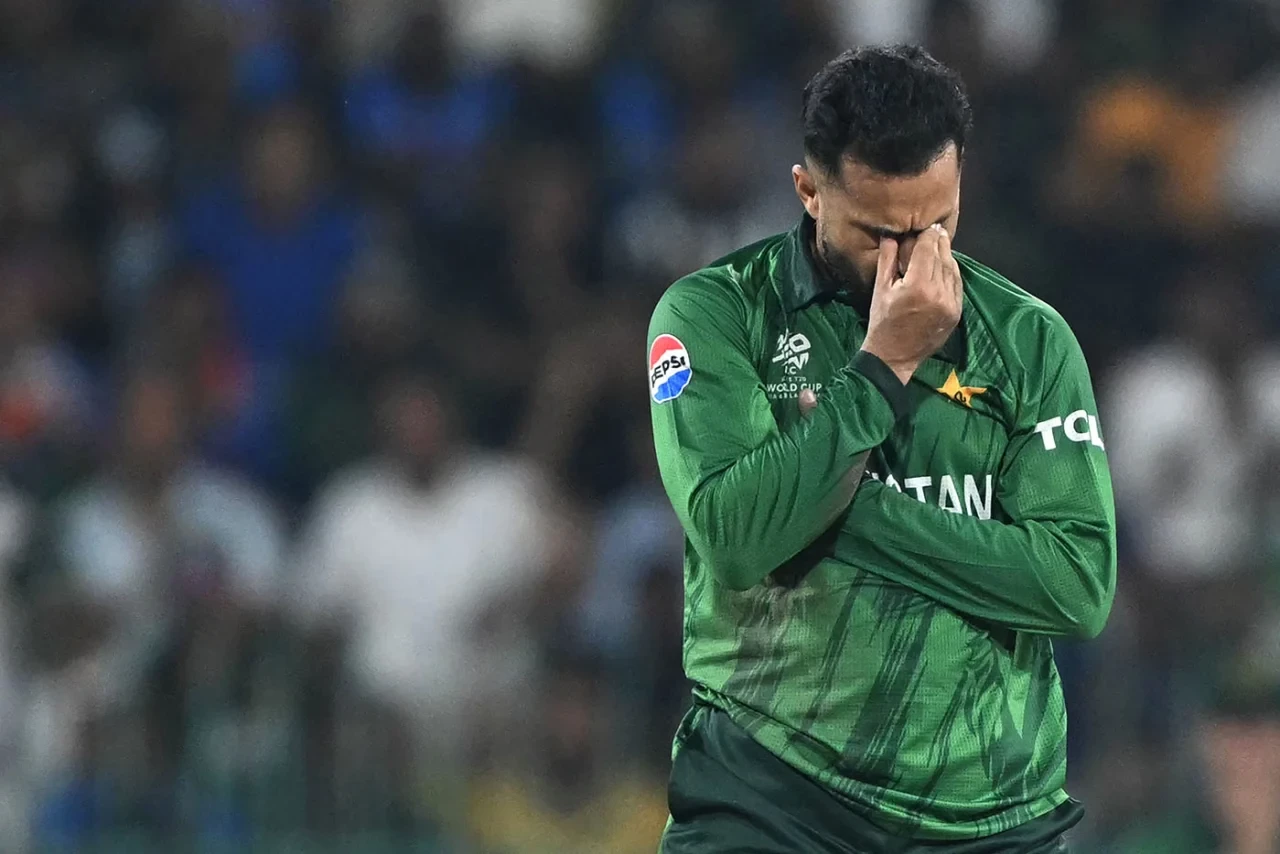

By the time the day of the match against India finally arrived, it carried not only political residue but emotional investment. When Pakistan lost by a clear margin, the disappointment felt layered. It was not simply a group-stage defeat. It was a performance that unsettled belief.

Yet the campaign did not unravel. Pakistan went on to win their remaining three group matches and secure qualification for the Super 8. The standings remain favourable.

This piece is not about whether Pakistan should have played. It is about what the performance revealed once they did.

The India match as a psychological test

Strip away the noise that preceded it, and the match against India becomes something more revealing than a rivalry fixture. It becomes a study in temperament. Pakistan were not confronted by unfamiliar conditions or an unknown opponent. They were up against a side they have analysed repeatedly, prepared for precisely, and competed against in multiple ICC tournaments. The gap that emerged did not feel technical. It felt internal.

From the early overs, there was a difference in posture. India’s intent was visible. Their batters looked decisive in stroke selection, clear in placement, certain in tempo. Pakistan, by contrast, appeared measured to the point of caution. Singles were taken where boundaries might have been attempted. Lengths were respected rather than challenged. The field dictated the play rather than forcing an adjustment.

Body language often reveals what scorecards conceal. There was no panic in Pakistan’s approach, but there was restraint. Shoulders dropped incrementally when pressure built. Conversations in the field looked corrective rather than proactive. Momentum shifted not in a dramatic collapse, but in phases. An over conceded quietly here, a scoring opportunity passed up there. The match drifted before it tilted. India dictated the tempo. Pakistan responded to it.

That is the difference between being outclassed and being inhibited. Pakistan were not overwhelmed by superior skill in every department. They were hesitant at decisive moments. Against the strongest opposition, that hesitation becomes the margin.

Tactical shortcomings in key phases

If the psychological layer framed the contest, the tactical details sustained it. Pakistan did not unravel in one reckless passage of play. They conceded ground gradually, across phases that in modern T20 cricket are designed to be seized rather than survived.

The powerplay remains the first inflection point. Pakistan’s starts were controlled but cautious. Dot balls accumulated, and with them came a subtle shift in pressure. The early overs did not collapse the innings, but they narrowed its possibilities. In contemporary T20 cricket, the powerplay is less about preservation and more about assertion. Pakistan leaned towards the former. India capitalised on that restraint by keeping fields attacking and lengths disciplined.

The middle overs exposed structural rigidity. Pakistan’s template continues to rely on anchors to stabilise, but when stability turns into stagnation, tempo suffers. Strike rotation slowed at key moments. The batting order appeared fixed rather than adaptable to matchups. Instead of promoting aggression when the field spread, consolidation persisted. Against elite bowling, that caution reduces scoring avenues and delays acceleration until it becomes forced.

Bowling phases followed a similar pattern. There were no glaring errors, but execution at the death lacked precision. Variations did not consistently deceive. Lengths missed by inches at crucial junctures. In T20 cricket, those inches convert into boundaries.

Fielding completed the picture. A misfield here, a slightly delayed release there. Marginal lapses that rarely headline a defeat, yet collectively concede ten or fifteen runs. At this level, that margin alters momentum.

The issue was not one catastrophic error. It was cumulative conservatism across phases that demanded controlled aggression.

Talent versus mindset

On paper, Pakistan is not a limited side. The bowling attack carries pace, variation and experience in equal measure. The top order includes players who have scored heavily across formats and conditions. The middle overs have power hitters capable of shifting games in a handful of deliveries. The three group-stage victories underlined that ability. Against other opponents, Pakistan looked balanced, confident and technically secure.

Which raises the uncomfortable question. Why does that assurance narrow against elite opposition? The difference is rarely about skill. It is about posture.

Sides such as India and England operate with visible permission to take risks. Their batters attack fields even after a mistimed shot. Their bowlers attempt yorkers and slower variations even after one is struck for four. Mistakes are absorbed as part of a larger intent. The tempo rarely retreats.

Pakistan, by contrast, often recalibrates after error. A boundary conceded tightens length. A false stroke encourages consolidation. The instinct shifts towards control rather than escalation. In isolation, that instinct is understandable. In high-level T20 cricket, it becomes restrictive.

This is where mindset intersects with method. When the objective subtly becomes avoiding mistakes rather than creating pressure, tempo alters. Singles replace calculated aggression. Safe overs replace probing ones. The game is managed rather than shaped.

The team does not lack ability. It lacks freedom under pressure. Against most sides, structure is enough. Against the strongest, freedom becomes essential. Until Pakistan align their evident talent with a willingness to sustain risk, the gap against elite opponents will continue to feel psychological rather than technical.

The Babar Azam and Namibia question

If the India defeat sharpened scrutiny on the team, it inevitably sharpened scrutiny on its captain. Babar Azam did not bat in the chase against Namibia, a decision that on the surface appeared practical. The target was modest, the platform secure, and giving a youngster exposure could be framed as investment in depth. Tournament management often demands rotation.

Yet timing shapes interpretation. After a high-profile defeat, even routine decisions acquire weight.

Babar’s role during the past tournaments has already shifted more than once. He was initially asked not to open, moving to number three in an attempt to recalibrate tempo. That adjustment was later altered again by the head coach in this tournament, and now some ex-players are asking for his retirement. For a player whose T20 record remains among the strongest in Pakistan’s history, both in terms of aggregate runs and consistency, such positional instability can create its own uncertainty. When structure changes repeatedly, clarity narrows.

The Namibia game added another layer. A youngster such as Khawaja Nafay was in the conversation, and when Babar did not come out to bat, questions followed. Was it tactical rest? A move to protect rhythm? An attempt to ease pressure? None of these interpretations require accusation, yet all circulate in the absence of explicit explanation.

Leadership narratives are rarely static. In big tournaments, they evolve quickly. Babar’s tempo in high-pressure matches has been debated before, not in terms of ability but in terms of pace relative to modern T20 expectations. Perhaps the broader question is one of format alignment. With his technique and temperament, he remains an asset in longer formats. Continuing to recalibrate his T20 role amid public scrutiny risks unnecessary damage to a record that still commands respect.

After a defeat of this scale, leadership clarity becomes part of the performance discussion itself.

The paradox of progression

It would be unfair to reduce Pakistan’s campaign to a single defeat. After the loss to India, the team did not unravel. It regrouped. It won the last group match. It secured qualification for the Super 8 without last-day dependence or mathematical anxiety. On paper, that reflects control.

In those matches, improvement was visible. The bowling regained sharpness. Lengths were more disciplined, plans clearer. The fielding tightened, cutting down the marginal runs that had slipped earlier. Batting intent appeared more aligned with the match situation. Confidence, often fragile in tournament environments, returned steadily.

This is the paradox. Pakistan did enough to progress. They showed that the squad has balance and resilience. The dressing room did not fracture under pressure. Corrections were made. Momentum was restored.

And yet, the India match continues to frame evaluation. Not because it was decisive in standings, but because it represented the highest competitive bar encountered in the group. It exposed hesitation against a top-tier opponent. That exposure lingers longer than comfortable victories over others.

Group-stage success confirms competence. It does not automatically confirm championship readiness. Tournaments escalate in intensity and precision. Margins narrow. Opponents adapt quickly.

Qualification masks inconsistency. It does not resolve it. Pakistan have earned their place in the Super 8. The question now is whether they have addressed the pattern that surfaced when the stakes first rose.

The Super 8 as identity test

The Super 8 phase will strip away comfort. New Zealand offers structure and discipline. In the group stage, it has largely outclassed its opponents, asserting control in most of their matches, with only South Africa managing to push them into deeper waters. That consistency makes them a different kind of challenge. Against New Zealand, Pakistan’s tempo management will be under direct scrutiny. A cautious start will not go unchallenged, and small tactical errors will be absorbed quickly.

England presents a different examination. It’s template is assertive from the first over. It attacks fields, reshuffles orders, and accepts risk as structural. If Pakistan retreat into conservatism, England will accelerate past them. Matching intent without losing control becomes essential.

Sri Lanka introduces tactical variation. Spin-based disruption, changes of pace, and calculated pressure in the middle overs will test Pakistan’s strike rotation and patience. Against it, stagnation can be as damaging as recklessness.

The pressure may not feel as politically and emotionally charged as it did against India, but the technical demand will be higher. Against New Zealand, England, and Sri Lanka, Pakistan will require their best skills, not just flashes of them. There will be less noise, but greater scrutiny in execution.

The boycott debate asked whether Pakistan would play. The Super 8 will ask whether they can play without restraint.