Business reporter, BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTaxes may have to rise in the autumn, economists have warned, despite big welfare cuts and spending reductions in Wednesday’s Spring Statement.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves is expected to meet her self-imposed rule to not borrow to fund day-to-day spending with room to spare, according to the government’s official forecaster.

But it has warned that global uncertainty due to the impact of US President Donald Trump’s tariffs could hit the UK economy and derail Reeves’s plans.

In that scenario, it would be difficult to cut spending further or borrow more so tax rises would likely be needed to meet her rules, experts say.

“Non-defence spending can only be cut so far. And the UK’s uncomfortable concoction of low economic growth and high interest rates means public borrowing can only rise so far,” said Paul Dale, chief UK economist at Capital Economics

“The inevitable conclusion is that at some point the government may have to break its election promises and raise taxes for households – the full Budget later this year will be the next flashpoint.”

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank, said the fact that Reeves had little room for manoeuvre “leaves you at the mercy of events”.

“We can surely now expect six or seven months of speculation about what taxes might or might not be increased in the autumn,” he said.

Reeves raised taxes for businesses in her first Budget in October, and when asked if there could again be tax rises in the Budget this autumn, she said: “We’ll never have to do a Budget like that again.”

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) also halved its growth forecast for the UK this year to 1%, down from its October prediction of 2%.

“I am not satisfied with these numbers,” said Reeves, who has made growing the economy one of her key promises.

However, the OBR raised its growth forecasts for the following years and Reeves said by 2029-30 the economy would be bigger compared to the forecast at the time of the Budget in October.

Tariffs impact

Ahead of the Spring Statement, the chancellor had been under pressure, with much speculation over how she would be able to meet her self-imposed fiscal rules. The two key ones are:

- Not to borrow to fund day-to-day public spending

- To get government debt falling as a share of national income by the end of this parliament

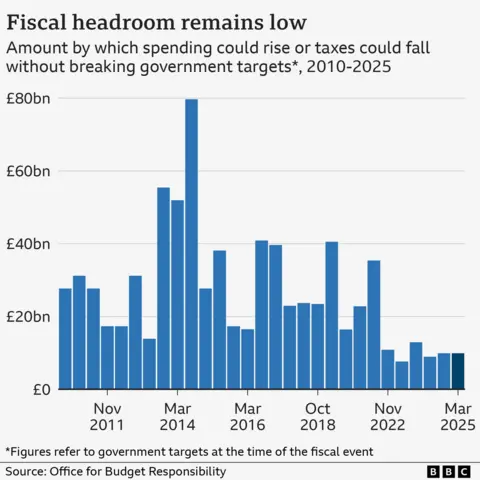

In October, the OBR said that Reeves had £9.9bn headroom by 2029-30 with regards to day-to-day spending – the amount left over after meeting the fiscal rule.

The chancellor said that changes in the global economy had altered the picture since then and she would have missed that rule by £4.1bn due to an increase in government borrowing costs.

However, the measures announced on Wednesday “restored in full our headroom” to £9.9bn, she said.

The OBR acknowledged that risks around the global outlook had intensified since October.

“If the US levied an additional 20% tariffs on the UK and the rest of the world, that could reduce the level of UK output next year by 1% and also wipe out the headroom that the chancellor has retained against her fiscal rules,” the OBR’s Richard Hughes told the BBC.

The £9.9bn is the third lowest margin a chancellor has left themselves since 2010. The average headroom over that time has been £30bn.

Regarding the second rule, Reeves said the OBR had forecast it would be met two years early, with a headroom of £15.1bn by 2029-30.

Looking at growth over the next few years, the OBR now expects the economy to grow by 1.9% in 2026, by 1.8% in 2027, by 1.7% in 2028 and by 1.8% in 2029.

However, Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said he thought the OBR would “almost certainly have to cut potential growth forecasts” in the autumn and also expected a rise in planned defence spending by 2027.

“So further tax hikes and borrowing are coming,” he said.

Real household disposable income per person is expected to grow by an average of around 0.5% a year, the OBR said. The forecaster said stronger wage growth meant this figure was slightly higher than in its previous prediction in October.

Reeves said this meant that by 2029-30 people would be on average more than £500 a year better off compared with what the OBR had expected in October.